In recent times, the hymn of many institutions has been more, more, we need more women in business, parliaments, and in power. Given the slow speed by which the number of women is growing in these institutions and positions, there are increased calls for efficient methods to reach gender equality. A quota system is a method that increases the number of women with the hope of reaching gender equality. At the same time quotas raise serious questions and, in some cases, even strong resistance. The main idea behind the quota system is to recruit women into (political) institutions and to ensure that women are not just tokens within the environment that they are placed in. Between 2014-2019, women’s representation lies at 36.2% of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), that is 12 points above the world average of national parliaments (24%) and 7 points above the European average (29.8%). Currently, the aim of many institutions is to reach 30% of women’s representation.

But why is women’s representation important? And if we reach gender parity, will that be enough? Let us have a look at what male-dominated industries tell us about women.

Architecture

The architecture field has been remarkable, because over the past decades the same number of men and women graduate for architectural studies. However, women almost entirely disappear from this field. According to researchers, there are different reasons for why women vanish from this industry: (1) they are being overlooked or ignored to the point where they feel invisible, (2) women at some point become mothers, (3) they are being patronized and valued for their appearance rather than their work, and (4) they are not given the full range of responsibilities intrinsic to their role, which hinders their professional development. On Instagram, I asked if people could name female architects: no one could name a female architect. On top of that, a quick search on Google on “famous architects” in Dutch, listed a top 10 of white male architects. I think that the latter two findings give voice to the problem within the industry: no representation of women.

Art

The other day I was watching the news and it was about women in art. In the Netherlands, we know many renowned painters, such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Vincent van Gogh, Piet Mondriaan, and Johannes Vermeer, but female painters are largely missing up until this day. For example, in the Netherlands, only 13% in art galleries is created by women. On the news, they also discussed that similarly to the architecture industry, the work of women’s artists has been for a long time not being taken seriously and is still less valued in $ compared to that of men. Despite increasing numbers of women’s artists, the industry remains a boy’s club.

Medical Science

Women have been excluded for centuries from medical and science knowledge production. So, essentially, we are left with a healthcare system that has been made by men for men. The history of medical science shows that the way women’s bodies have been sketched are in line with the reproductive discourse: women’s hips are much wider and their heads way smaller. As this industry was led by men, Dr Janine Austin Clayton, an associate director for women’s health research at the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), told the New York Times that the result is:

“We literally know less about every aspect of female biology compared to male biology.”

To me, the medical science industry demonstrates clearly why women’s representation matters. Medical scientists are still researching medical problems with different symptoms for men and women. Female medical scientists and doctors stand at the front to address healthcare issues that are overlooked for women. Diseases presenting differently in women are often missed or misdiagnosed, and those affecting mainly women remain largely a mystery: understudied, undertreated and frequently misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. This has consequences for both medical practice and the health of women.

Hence, male-dominated industries teach us that the view of women is still based on old narratives: women are valued for their appearance, and they should not be taken seriously. Their work and presence are not valued in the same way as that of men. With a lack of female representation in the industries, many women flee to other sectors and are forced to give up on their passion and dreams.

Should we look beyond the numbers?

Scholars have acknowledged that a lack of representation of women threatens gender equality and sustains unequal and unjust power relations in decision-making. Therefore, gender parity has become an important topic. While many institutions focus on the 30% women quota, the current debate in the academic literature has shifted towards whether we should or should not focus on the number of women elected and/or appointed.

After all, not every woman is a feminist and wants to engage with women’s related issues. Just because someone is a woman does not mean that she is an advocate for all women. Not all women believe in the same things. Not all women act in the same way. Therefore, some scholars argue that people should be put in place who are the right fit for gender equality. This includes feminist men. According to them, we should not be focusing on increasing the number of women, because it does not ensure gender equality.

Although they have a point in arguing that equal numbers of men and women ≠ gender equality, that does not mean that there should be less focus on increasing the number of women. History has shown that female elected representatives tend to look out more for women. In the 1990s, women MPs led the way for parental leave and equal pay. Similarly, the medical industry has several female experts committed to women’s health issues.

Let us assume for a moment that feminist men are committed to menstrual leave, longer maternity leave, equal pay, getting more women in top positions etc. They join panels on TV and represent women. Would women feel valued, heard or seen? They might feel valued and heard, but not SEEN. And this is what women’s representation is about. It is about VISIBILITY, being present in spaces where important decisions are being made and where important things are discussed. It does not matter what the topic is or whether a woman is interested in women’s related issues. It is about knowing that as a woman, you can hold a position of power, your work is valued in the same way as the work of men is valued, your presence matters, and you have equal chances of becoming a manager, sports reporter, or minister president as men have.

The male-dominated industries have shown the impact of centuries of male supremacy on the perception of women, which is the reason why we are talking about women’s representation today. The fact that there has been a focus on gender equality for decades now and many institutions still struggle with reaching a board that exists 30% out of women, shows the need for effective methods, such as the quota system. People who are against this system say things like “people should be chosen because of their capabilities and qualities not because of their gender.” I agree with this, I think that people should be chosen based on their capabilities, but if after all these years we have to conclude that more men get chosen over and over again. Maybe we should critically examine the type of society we live in to understand why men get picked over women to fill these positions. Perhaps they are the ones who get picked because of their gender and not because of their capabilities?

I don’t say this to attack men. I am convinced that there are men out there who are excellent in their work. What I am trying to say is that people are so used to see men as leaders or experts that men automatically get selected. It has become so normalised to see men in certain positions that to even imagine a woman in those positions is unthinkable. As a result, her capabilities are easily overlooked, whereas a man who is less capable is selected just because he is a man. And this could be a reason why it is taking decades to increase the number of women.

To tackle gender inequality, we need women, feminist men, and education to change institutional hierarchies and to overcome cultural, socioeconomic, and structural barriers.

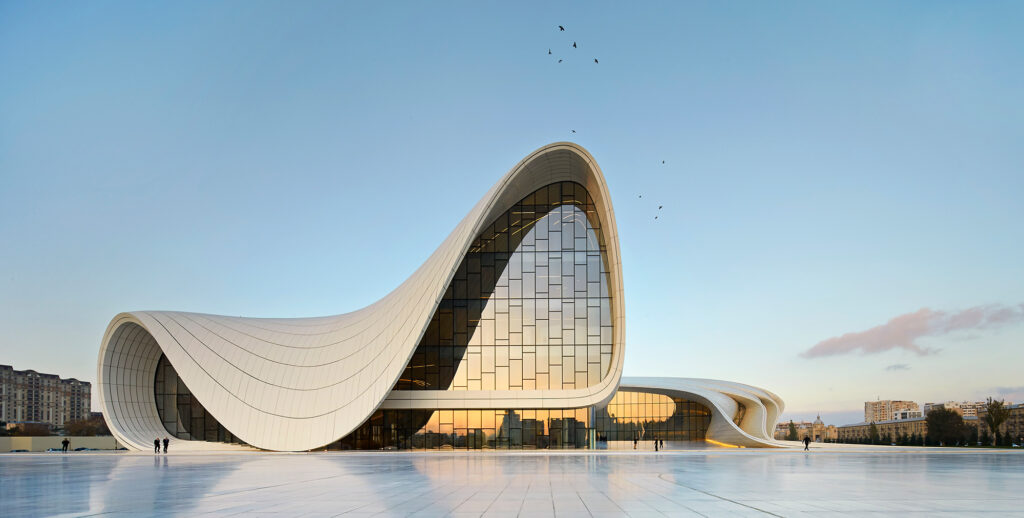

I could not leave you all behind without giving you names of female architects.

Right: Jeanne Gang – Aqua Tower in Chicago, USA, Source: Inhabitat Diane Pham

References:

Karen Burns, & Lori Brown. (2020). Telling Transnational Histories of Women in Architecture, 1960–2015. Architectural Histories, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.403

Cole Graham. (2017). Where gender equality remains a myth, minority representation of women in architecture. Human Resource Management International Digest, 25(2), 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-01-2017-0011

Jackson, G. (2019). The female problem: how male bias in medical trials ruined women’s health. The Guardian.

Larson, A. R., Sharkey, K. M., Poorman, J. A., Kan, C. K., Moeschler, S. M., Chandrabose, R., … & Nazarian, R. M. (2020). Representation of women among invited speakers at medical specialty conferences. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(4), 550-560.

Meesterlijke vrouwen. https://www.stedelijkmuseumschiedam.nl/tentoonstelling/meesterlijke-vrouwen/